Lorenda Taylor knew the stakes were high for this trip, so she couldn’t forget to pack a thing. It had taken about a month to make this list and now everything had to be accounted for and checked off. Nothing could be missed. The list was life.

In went the medicine for asthma. Drugs for chronic bronchitis. Pills to prevent lung inflammation. A few more treatments for high blood pressure. A blood vessel relaxer, too.

She checked the equipment that would be making the journey with her. The most critical was the portable oxygenator that would puff air into her nose. No equivocation - that had to work. Taylor packed four rechargeable batteries with it to ensure she could make the long drive and flight from her home in Mobile, Alabama, to Amgen’s headquarters in Thousand Oaks, California. It would be about a 12-hour journey, all told.

“You can’t wing this,” Taylor said. “If I get it wrong, the flight could be grounded or forced to land due to a medical emergency.”

Taylor sat on her couch, carefully separating and sliding the medicines into clear Ziplock bags. She had done the research – checking with the airlines and the U.S. Transportation Security Administration to make sure she could carry them all on board the flight with her. “This is how they said to do it,” she said with a bemused tone and zipping closed another bag.

And that was the other part of this complicated equation: For all of the preparation to make this trip and the pressure of not forgetting critical, life-dependent items, Taylor was doing all of this for the first time in her life.

Many things had changed in a post-9/11 world and few things had changed more than air travel. The last time she traveled on a commercial flight was 25 years ago – a few years before 9/11 changed everything.

“I flew a bit before that,” she said. “I flew to Seattle in 1998. I worked for FedEx and flew in the jump seat on one of their planes. But this is a whole new thing.”

Taylor looked around her living room. There was a short, pink table with Disney princesses on it for when her granddaughters came to visit. Next to it was a dollhouse. A television where she liked to watch – and binge – a variety of shows, including “Loki” and “Wheel of Time” and “Ghosts.”

She had been awake since 5 a.m. and hadn’t slept that well with the trip weighing on her mind. In her determination to not forget anything, she didn’t remember she had left breakfast uneaten in the kitchen.

Too late for that. It was about time to leave.

Taylor eased herself up with help from a walker and pulled her suitcase across the threshold of the front door and put it on the porch. Then she went back and slowly walked out, pulling the oxygenator with her.

A black SUV parked in the driveway waited. Taylor paused and took a breath. The SUV’s driver, Brandi Paige, and Lorenda’s aunt, Clarice Coleman, helped her with the luggage as she took the slow steps toward the vehicle. When she was inside, she fitted the oxygenator next to her by her feet. She looked out the window at the neighborhood she’d lived in for close to three decades.

“OK,” she said quietly. “Let’s go.”

Lorenda Taylor walks towards a vehicle carrying her oxygenator as she prepares to leave for Los Angeles from her home in Mobile, Alabama. Dan Anderson/Getty Images for Amgen

Mobile to New Orleans

Taylor had been asked by Amgen if she would be willing to participate in the company’s Mission Week in 2023 as a panelist talking about what life is like living with severe active ANCA-associated vasculitis.

The biggest crowd she’d spoken to before was at her church in Mobile and the audience for Mission Week would be an auditorium with hundreds packed into it – along with a livestream that would also be recorded so the company’s employees around the world could watch and hear her story.

“Vasculitis is unfamiliar to most. We knew we needed a special individual that could not only explain the lived experience of the disease but bring the disease to life for the first time for so many,” said Stephen Marmaras, Advocacy Relations director at Amgen. “Lorenda’s warm and relatable approach to storytelling invited our audience into her world and encouraged them to learn from it and act on it.”

Taylor said she thought she wanted to help others – as well as meet people at Amgen to talk to them about their work and to thank them for medicines she was taking. Speaking about her journey and educating people on vasculitis felt empowering.

“This thing, vasculitis, is not just one thing in itself,” she said. “Because of vasculitis I have interstitial lung disease – namely COPD and asthma. Because of vasculitis I have chronic kidney disease. Because of vasculitis, I have problems with bronchitis and sinusitis. It’s not just the one thing.”

Inside the SUV driving toward New Orleans – the closest big airport to Mobile and about a two-hour drive – she kept her mind occupied with things other than the logistics of the trip. But the questions were lodged in her head: Would there be a wheelchair waiting for her when she arrived? Would TSA screening be quick enough so she didn’t have to stay on her feet too long? On the plane, would she be able to access medicine and how would the oxygenator fit? What if the flight was delayed and she couldn’t get the batteries charged?

Paige, driving smoothly west on Interstate 10 past large swaths of undeveloped land that, in some places, quickly turned to swamp, asked Taylor if it was her first trip to Los Angeles.

It was.

They talked about things to do in Southern California, though Taylor was unsure what her schedule would allow – and, more importantly – what her body would consent for her to do. They compared cost of living in Los Angeles to Alabama. “I don’t know how you all do it,” she said with a laugh when told the vast price difference in rent, groceries and gasoline.

She looked down at the oxygenator that plugged into an outlet in the SUV – an attempt to save battery life while making sure it was fully charged when she got out of the car. She decided to check to see if the battery was full. She slipped the clear tubing nosepiece in and the air flowed.

But the green light on the oxygenator showed the battery hadn’t been charging the entire time.

She turned to Coleman.

“I may only have three batteries for the oxygenator,” she said. “I don’t know why it isn’t charging.”

She unplugged it and changed the setting on it, which slowed the flow of oxygen into her nose as way as a way to extend the battery’s life. She fidgeted with the part of the tube that hooked around her ears, making room for them with the earpiece that connected her cell phone that started to ring.

She laughed, putting it around her ear, noting it was lucky she wasn’t trying to read anything, too.

“I sometimes think there is only so much I can hang on my ears,” she said. “Oxygen, reading glasses, phone.”

It was her son, checking in on how she was doing and to wish her a safe trip. She spoke with him for a few minutes, recapping the packing and ride so far. Asked him about his job. He made her laugh. She said she would call him when she landed in Los Angeles.

When she hung up, she grew quiet and looked out the window as Lake Pontchartrain glistened in the Sunday morning sun. A lone fishing boat bobbed amid small waves. Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport was about a half-hour away.

Her mind was already there, wondering how much the airport had changed since 1998. How much she had changed since 1998, when her life wasn’t dependent on a steady flow of oxygen from a tank. And how much this all would change her once she made it to Thousand Oaks.

Lorenda Taylor is driven from Mobile, Alabama to New Orleans to catch her flight to Los Angeles. Dan Anderson/Getty Images for Amgen

The Airport

Almost 6 million people used Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport in 2022 and little of it resembled what Taylor remembered.

The airport had gone through major renovations in 2019, reopening with a $1.3 billion terminal that featured large paintings of Louis Armstrong, jazz-themed instruments and restaurant names closely tied to New Orleans: Café Du Monde, Emeril’s Table and Mondo.

As the car pulled up to the curb, Taylor looked out the window for the wheelchair that she’d need.

Paige got out and started to unload the luggage. An airport employee soon arrived with the wheelchair. Taylor eased into it, maneuvering her oxygenator to the side so Coleman could push it parallel to her. The glass doors opened as they rolled into the airport.

At the ticket counter, she waited as the Delta employee double-checked the paperwork on her oxygenator. They cross-matched it to ensure it was approved by the Federal Aviation Administration. They checked to make sure the forms had been submitted 48 hours prior to her flight. They checked to make sure her batteries had a 150% of battery life for the cumulative flight time. She showed them the forms that showed she had the required batteries and inspected the valves and connections.

She was nervous, with all the extra items in her checked bag, that it would exceed the 50-pound weight limit.

The Delta employee smiled. It was 48 pounds.

Taylor collected her baggage claim tags. The airport employee turned and wheeled her to the TSA check area.

Clarice Coleman, Lorenda Taylor's aunt, helps push the portable oxygenator through the airport in New Orleans on their way to the boarding gate. Dan Anderson/Getty Images for Amgen

Security and Boarding

The line for a Sunday morning was light and Taylor watched as people took off their shoes and belts. They put laptops into gray bins. It was just like she’d seen in countless movies and television shows.

Because she was in a wheelchair, a TSA agent motioned to the airport employee pushing her to bring her through, letting her bypass waiting in line. She slipped through and suddenly was amid travelers hurriedly trying to keep up with their belongings moving along a conveyer belt into a scanner.

Coleman and the airport employee helped Taylor with her shoes.

In her mind, she was hoping for patience. “I wanted it to all go smoothly the first time around. I didn’t want to look uncooperative.”

The TSA Agent asked Taylor if she’d be able to stand on her own – without the oxygenator – to go through the body scanner.

Yes, she said. The agent asked if she would be able to hold her hands up over her head. Again, yes.

She took the oxygen tube from her nose and slowly rose to her feet. She entered the body scanner and lifted her hands over her head. She felt herself getting tired from holding her hands up for those few moments. Not too much longer, she thought.

And then it was over.

Her bags with medication went through the X-ray machine. The airport employee was ready with the wheelchair and she sat down and slowly slid the oxygen tubes into her nose again. Her shoes were put back on again and the oxygenator vibrated with life. Clutching her boarding pass, Taylor was wheeled down a long hallway with large windows that let the sunlight stream through the airport. Coleman walked alongside her, wheeling the oxygenator.

She looked along the walls. “Lots of Saints stuff,” she said, noting the souvenirs, pictures and decorations featuring the NFL team from New Orleans.

At the gate, she checked in and the Delta Airlines employee explained how she would be among the first to board and double-checked to make sure the oxygenator would fit and that she’d be able to access the aisle in case of an emergency.

Then it was time to fly. She plugged one of the oxygenator batteries into an outlet to make sure it was fully charged. Then she waited for the boarding announcement.

All of her preparation had brought her to this point.

Lorenda Taylor's flight prepares to take off at the airport in New Orleans. Dan Anderson/Getty Images for Amgen

‘Have a Good Flight’

Taylor was thinking about what she was going to say at Mission Week. She said she was an introvert growing up, but tried to force her way out of that when a high school classmate labeled her withdrawn tendency as “stuck up.”

She said she found one way through that was to be a good listener. With a warm smile and approachable demeanor, she said it wasn’t unusual for her to be somewhere and to have a complete stranger strike up a conversation with her.

“One time a lady started talking to me in the produce section about how her son had been murdered and his murderer was walking around free and she just started pouring out her pain,” Taylor said. “In my head, I’m just asking God to give me the words to speak and help someone who is hurting.”

These memories and thoughts reminded her that she was more than just her disease.

Taylor was a grandmother who read to her two young grandchildren and cared for them while their working parents needed a babysitter. She encouraged the children to use their imaginations as they pretended to be animals crawling around the living room floor in her house, recording them so their parents wouldn’t miss key moments.

And disease hadn’t taken her passions, either. Taylor would listen to music regularly – a wide variety that ranged from Nirvana to Prince to T-Pain. She was once an avid concert goer – seeing Prince twice and once seeing Michael Jackson – but the disease had made seeing live shows more difficult. She said she still dreams of seeing Coldplay live.

“I do grieve the old abilities at times,” she said. “I have to spend time in reality and then start focusing on what I can do.”

Part of that was the reason she was about to board the plane that would take her to California for the first time in her life.

“I have to remind myself there are things I still can do.”

The boarding announcement crackled through the speakers and Coleman helped collect the charging battery and wheeled the oxygenator next to her up to gate crowding with passengers waiting to board. She showed her boarding pass and the Delta ticket taker smiled and said words Taylor hadn’t heard said to her since 1998.

“Have a good flight.”

She was wheeled through the covered access walkway that led to the plane. She reached the doorway and stood up and took about 10 steps through the narrow accessway to the first seat in the cabin. Sitting next to Coleman, they made sure the batteries were accessible and any medications were easily reachable.

When the plane took off, she remembered what it felt like to fly after all those years. In many ways, that part hadn’t changed a bit. She took some photos with her phone of the land miles below her. It was an amazing sight. She listened to music: Lizzo, Chris Stapleton and Billie Eilish. She took a few naps. Her ankles had swollen a bit, but she said it wasn’t debilitating.

All that was left was to make sure there was a wheelchair waiting for her in Los Angeles.

Lorenda Taylor boards her flight to Los Angeles. It was her first flight in 25 years. Dan Anderson/Getty Images for Amgen

Journey’s End

The landing was smooth and long after all the other passengers had collected their belongings and left the aircraft, Taylor rose to her feet and walked about 10 steps to the cabin door. An airport employee was ready with a wheelchair. She sat in it and once she saw her baggage had arrived, she was able to relax more.

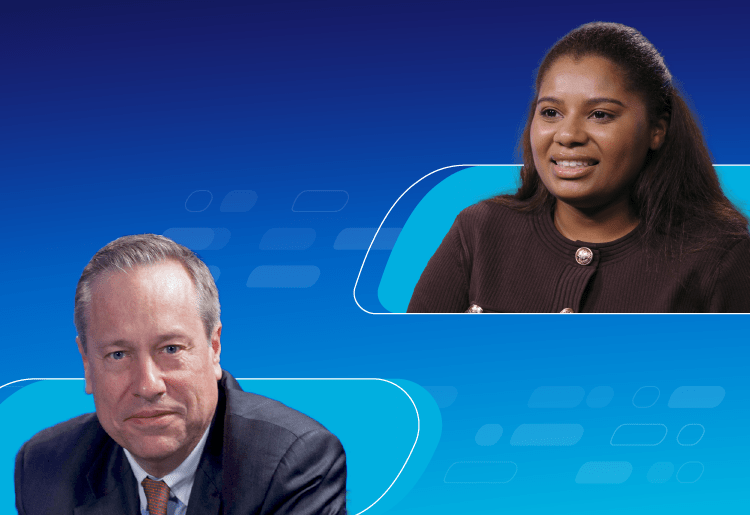

The oxygenator was still working and there was still a fully charged battery that would be available for the drive from the airport to her hotel in Thousand Oaks. Her day had started at 5 a.m. East Coast Time and wouldn’t end until around 6 p.m. Pacific Coast Time. She would take the stage at Mission Week two days later as part of the second panel hosted by Lisa Giuroiu, Amgen Advocacy Relations director.

Giuroiu introduced her that morning to the audience. Under her own power, Taylor took the final 16 steps of her journey that had begun at her home in Mobile. In her hand, she carried the oxygenator. The full auditorium applauded and cheered.

“Hello everybody,” Taylor said, settling into her seat.

Her long journey had ended. But Taylor’s life journey would continue on.

Lorenda Taylor at the panel in Thousand Oaks for Mission Week. Amgen file photo